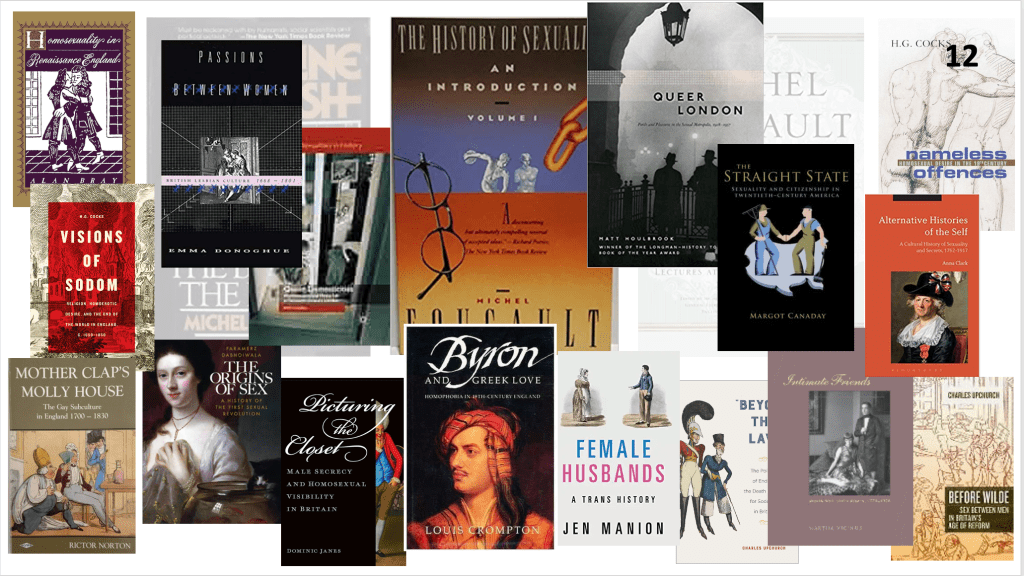

1 This paper has two main goals. First, it briefly outlines themes my current book project, ‘Called It Macaroni’: A British Queer History of the American Revolution. Second, I will argue why such an analysis is important for the project of queer history more broadly, arguing for the political aspects of what we think of as modern queer identity, and showing how politics, the public sphere, and understanding of the self have a consistency in how they influence understanding of same-sex desire from the late seventeenth century forward. I do this in part by calling attention to the histories of same-sex desire between women from the 1990s that focused on the long eighteenth century (as written by Anna Clark, Emma Donoghue, Martha Vicinus, Valerie Traub, and others). These works all argued that their evidence showed a form of identify formation around sexual desire in their period. When these histories are incorporated into the history of sex between men – rather than separated off and treated as something different, as they were in the early 2000s – then it can be shown that historians have been arguing for an uneven yet consistent process of forming self-understandings around same-sex desire and transing gender from the late seventeenth century forward.

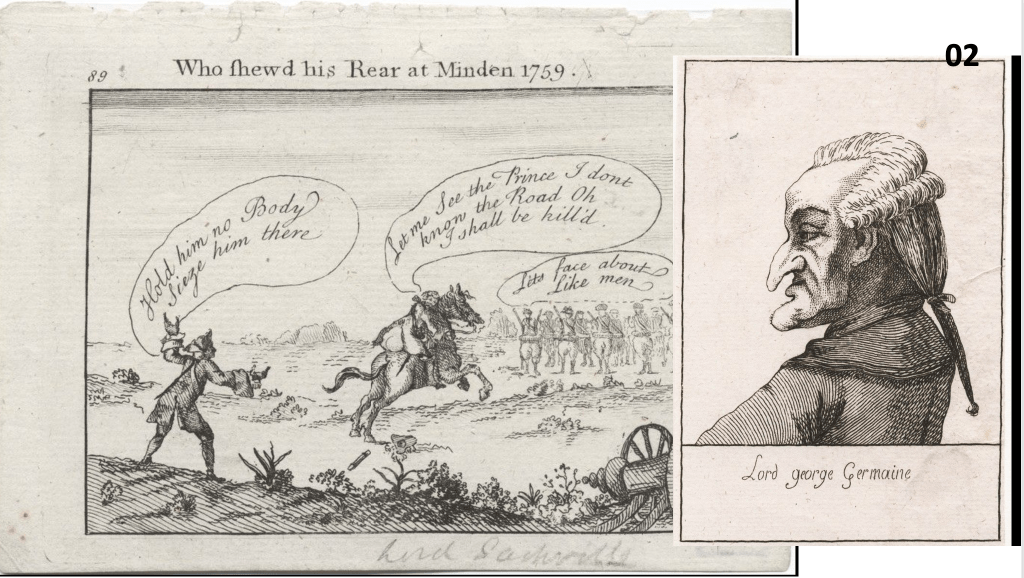

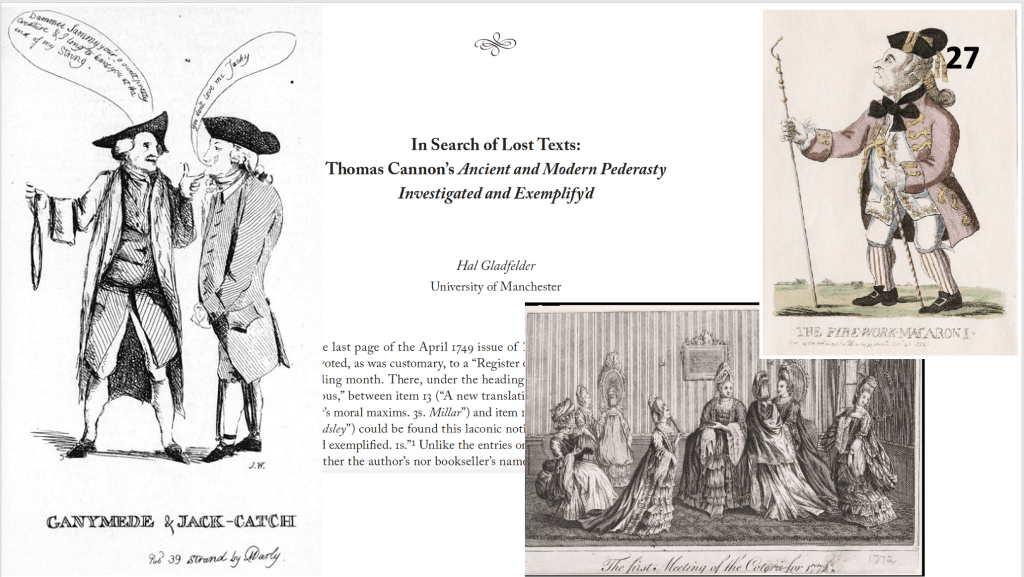

2 Within Britain in the 1770s and 1780s, public criticism of effeminate or sodomitical courtiers holding positions within the government and the military and sapping the national strength is not uncommon. Accusations were not enough to lead to the removal of an individual otherwise in good standing even when, as in the case of George Sackville (the viscount who coordinated British military operations during the American Revolution) such rumors were longstanding (in Sackville’s case dating to the Seven Years War) and acknowledged by later biographers as well founded.[i]

[i] See chapter two of Upchurch, ‘Called It Macaroni.’ Elements supporting this perspective can also be found in works such as Faramerz Dabhoiwala, “Lust and Liberty,” Past and Present 207, no. 1 (May 2010): 172–173; Faramerz Dabhoiwala, The Origins of Sex: A History of the First Sexual Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

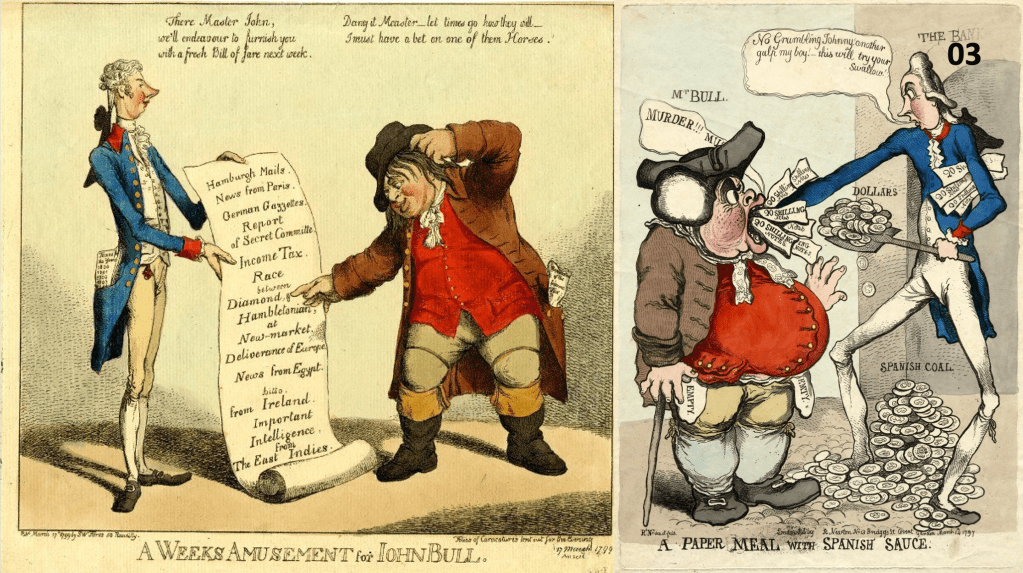

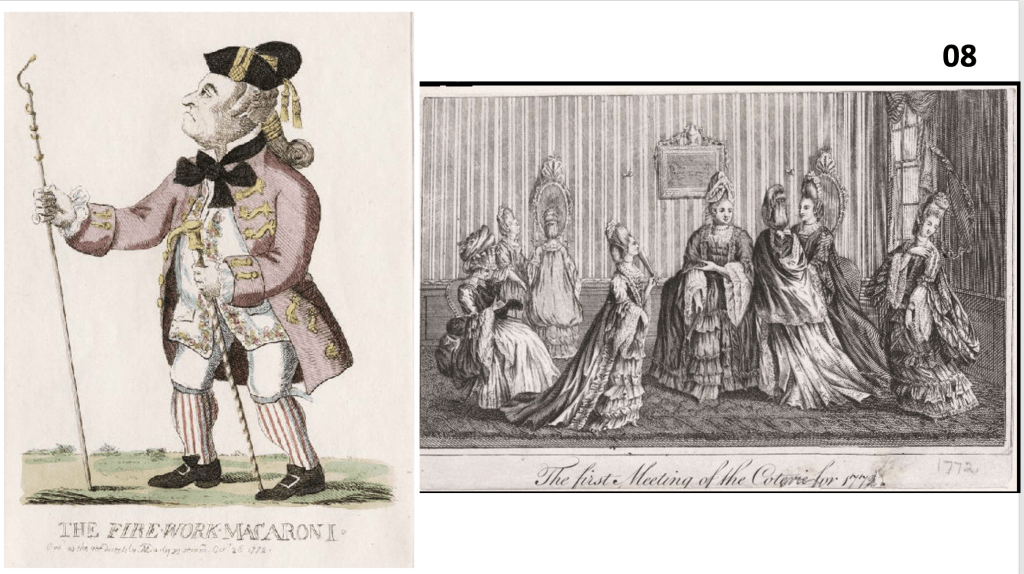

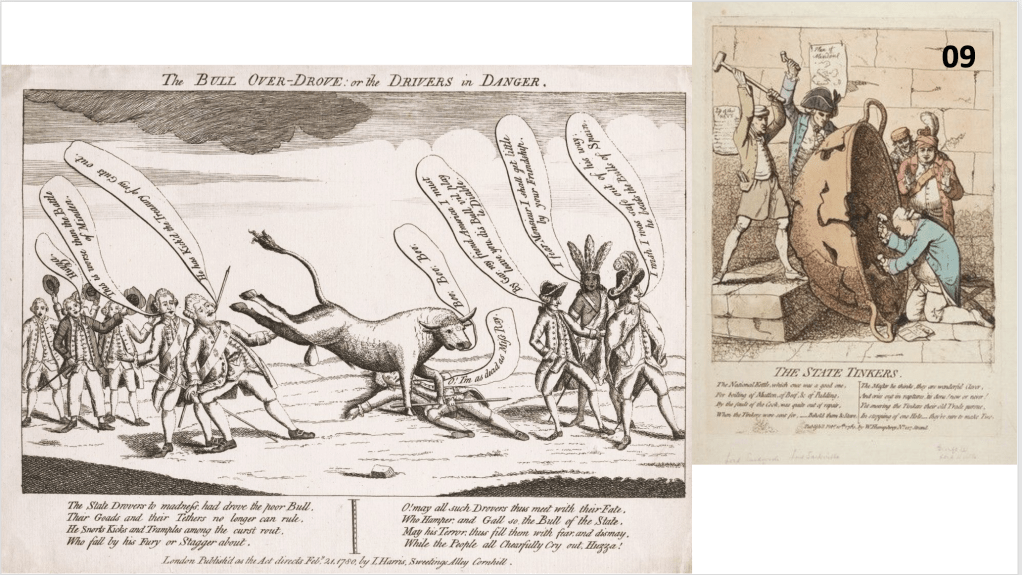

3 In these years, debates over freer versus more regulated trade, as well as other political issues, often played out within rhetoric of competing masculinities, sometimes depicted in provocative caricatures, pitting a rustic, simplistic, and straightforward “John Bull” against the sophisticated, effeminate courtier.[i]

[i] See chapter two of Upchurch, ‘Called It Macaroni.’ Supporting material for this can also be found in passing in works such as Hannah Barker, Newspapers, Politics, and Public Opinion in Late Eighteenth-Century England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998); Bob Harris, A Patriot Press: National Politics and the London Press in the 1740s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); Kathleen Wilson, The Sense of the People: Politics, Culture and Imperialism in England, 1715–1785 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

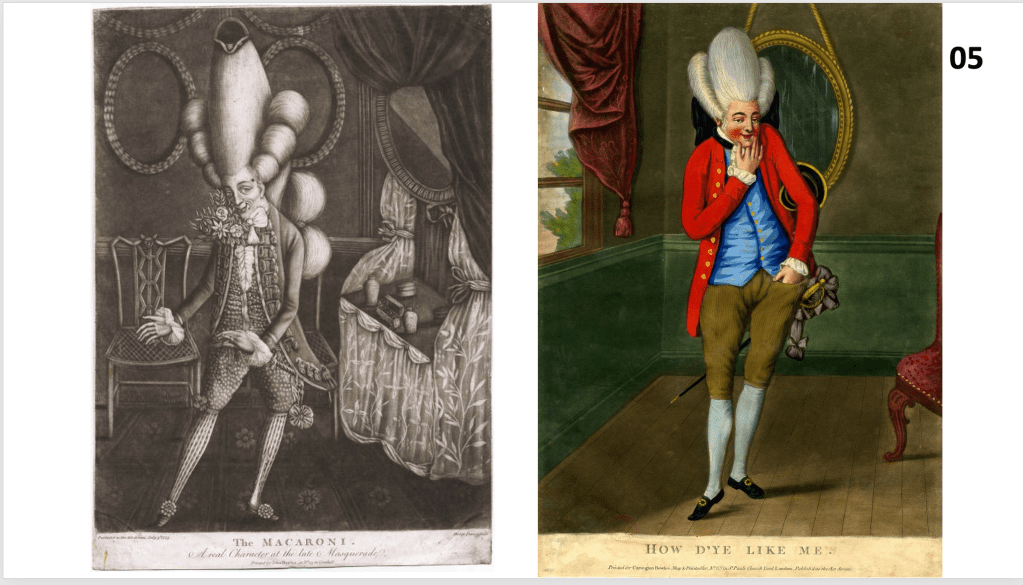

4 A touchstone in some of these debates was the adoption by men of the “macaroni” style of dress, which was considered effeminate and unmanly by many commentators.[i]

[i] Dominic Janes, Oscar Wilde Prefigured: Queer Fashioning and British Caricature, 1750–1900 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Dominic Janes, Picturing the Closet: Male Secrecy and Homosexual Visibility in Britain (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); Philip Carter, “Men about Town: Representations of Foppery and Masculinity in Early Eighteenth-Century Urban Society.” In Gender in Eighteenth-Century England: Roles, Representations and Responsibilities, edited by Hannah Barker and Elaine Chalus (New York: Longman, 1997), 31–57.

5 The Societies for the Suppression of Vice periodically paid for and publicized prosecutions of “molly houses” at this time, in order to shame the government into greater action against these establishments where men met for sex with each other.[i] In a dynamic not repeated in the nineteenth century, these prosecutions were designed to garner publicity, foregrounding salacious details as a part of a larger effort to influence the direction of the Church of England more broadly.[ii]

[i] See chapter three of Upchurch, ‘Called It Macaroni.’ Supporting material for this can also be found in passing in works such as Rictor Norton, Mother Clap’s Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England, 1700–1830, rev. 2nd ed. (Stroud, Gloucestershire: Chalfont Press, 2006); Anna Clark, “The Chevalier d’Eon and Wilkes: Masculinity and Politics in the Eighteenth Century,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 32, 1 (1998).

[ii] Charles Upchurch, “Liberal Exclusions and Sex Between Men in the Modern Era: Speculations on a Framework,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 9(September 2010): 409-431, and unpublished data currently being gathered for “Called It Macaroni.”

6 A number of famous actors and authors were at the center of widely reported scandals involving same-sex desire in these years, as well as regionally prominent gentry and clergy, with the details of their actions and the harshness (or not) of their punishments debated in the public sphere.

7 This was also the period that saw the earliest published debates over punishing men for sodomy in Britain. In 1749, Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplify’d attempted to defend ancient sexual practices and argued for their tolerance in the contemporary world. That work was suppressed, though, and all known printed copies destroyed.[i] Only recently have part of the contents of the publication been reconstructed.

[i] Hal Gladfelder, “In Search of Lost Texts: Thomas Cannon’s Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplify’d,” Eighteenth-Century Life 31, 1(Winter 2007): 22-38; Hal Gladfelder, “The indictment of John Purser, containing Thomas Cannon’s Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplify’d,” Eighteenth-Century Life 31, 1(Winter 2007): 39-61.

8 Another incident, however, recorded a significantly more tolerant approach to sex between men within a debate in the public sphere. It was sparked by the pardon of a man of fashion, who had been sentenced to death for sodomy. Dozens of letters to newspapers can be recovered for this event, recording a range of reactions, from individuals who argued that the executions should have been allowed to go forward, to those who argued that the state had no business punishing these acts, and that public distaste alone would be enough to keep them from becoming a common occurrence. One correspondent called the sodomy law “a political stink-trap, invented by Henry VIII, demolished by his daughter Mary, and restored by Elizabeth, during the contentions betwixt the clergy and laity for dominion,” and hoped for the day when it would be done away with, like the witchcraft and blasphemy laws.[i] While some objected to this issue being debated in public, others argued that it was a topic of universal interest, and needed to aired. This particular debate occurred in 1772, while others followed in subsequent years.

[i] “To the Printer of the Morning Chronicle,” Morning Chronicle, August 20, 1772. Other evidence presented in chapter four of Upchurch, ‘Called It Macaroni.’

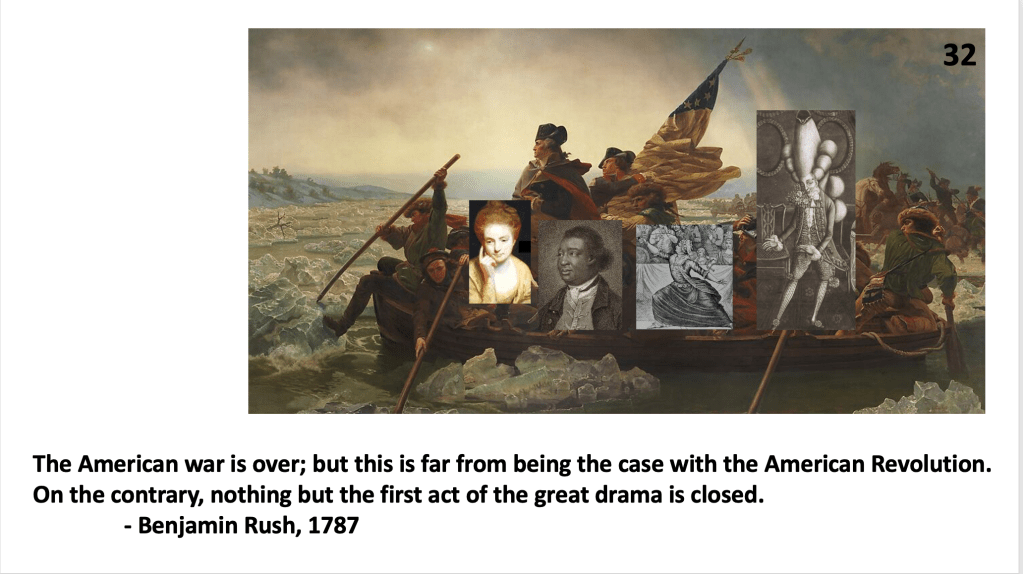

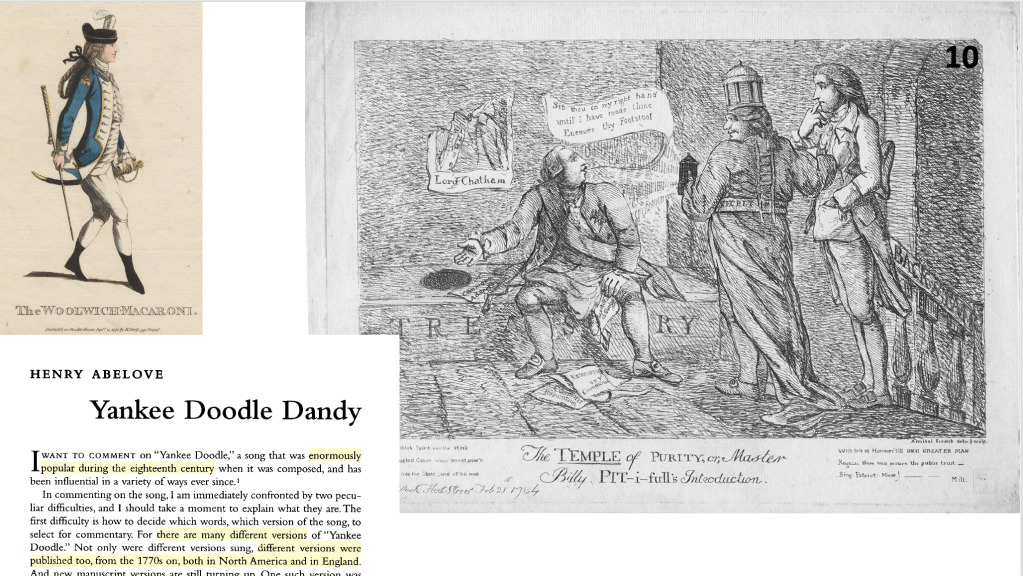

9 The war for American Independence brought many of these issues to a head, as the recriminations over a losing and then lost war facilitated new levels of criticism and acrimony, focused on both the government and general trends within society. Within the colonies themselves, others scholars have already shown the sexual politics of the song “Yankee Doodle” and its direct allusions to issues masculinity, self-control, and sexuality.[i]

[i] Henry Abelove, “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” The Massachusetts Review, 49 1/2(Spring-Summer, 2008): 13-21.

10 John McCurdy’s Vicious and Immoral has shown how, just before the outbreak of the war, the ideologies underpinning the revolution could be used to justify a man making use of his body as he sees fit, as a defense against a sodomy charge.[i] Just published work by Mary Sanderson in Gender and History has shown how, in the immediate aftermath of the war, anxieties over the rapid promotion of William Pitt the younger were expressed in caricatures alluding to Pitt as a catamite to George III.[ii] In short, their seems sufficient material on different aspects of sex between men published in the public sphere in this period to warrant a monograph-length study. Rather than flesh out more of these factual details, though, I’m going to spend the remainder of my time on the larger question of how this connects to the field of queer history in general. Why are events from the late eighteenth century relevant to the origins of modern homosexual identity, an identity that first formed, according to so much of the secondary literature, a hundred years later.[iii] Why are the events I described above important to, or even a part of, that narrative?

[i] John Gilbert McCurdy, Vicious and Immoral: Homosexuality, the American Revolution, and the Trials of Robert Newburgh (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024).

[ii] Mary Sanderson, “Sodomy, Corruption and Englishness: Politicising Sexuality in Satirical Depictions of William Pitt the Younger, 1784–1790,” Gender and History (June 2025): 1-14.

[iii] For statements of this argument related to the late nineteenth century, see H. G. Cocks, Nameless Offences: Speaking of Male Homosexual Desire in Nineteenth-Century England (London: I. B. Tauris, 2003). For statements related to twentieth century developments, see Margot Canaday, The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011).

11 To begin, it can be useful to review why it is argued that modern homosexual identity has its origins in the late nineteenth century. As explained by Michel Foucault, individuals can only form identities and self-understandings through the cultural texts that they have access to. While they might creatively combine and reconfigure existing cultural texts, and attempt to share those reconfigurations with others, the types of self-understandings possible in any given time or place are limited by the cultural material available. Foucault famously argued that it was in medical discourses that the idea that there was a specific type of person, a “homosexual,” rather than individuals who committed homosexual acts, took hold and was widely spread.[i]

[i] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality. Vol. 1, An Introduction (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

12 But we should remember that this formulation was first put forward by Foucault almost fifty years ago, at a time before all of these books were written.

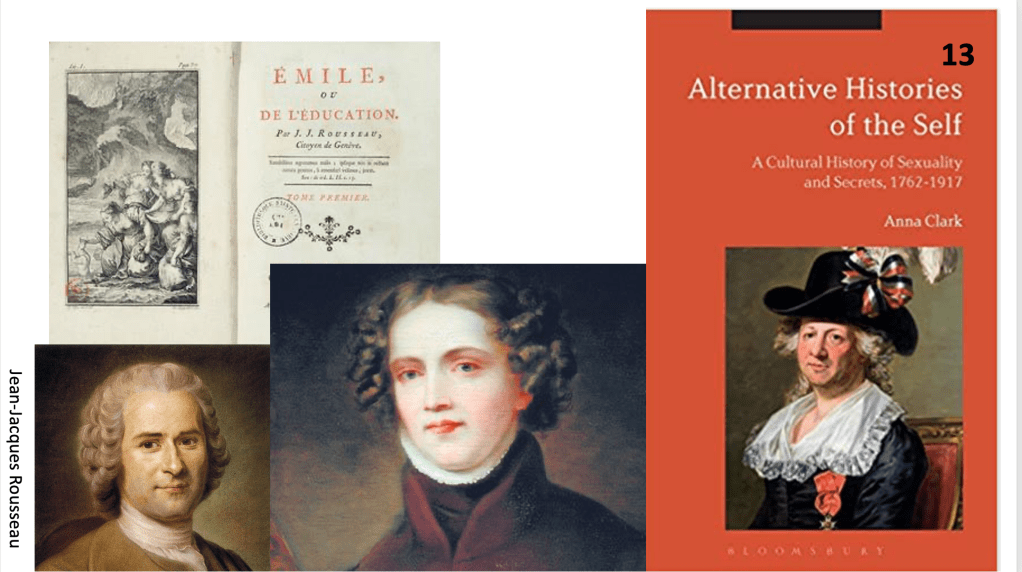

13 In particular, the work of Anna Clark on Anne Lister, has shown that in the early nineteenth century other cultural texts, such as Rousseau’s concept of the unique or expressivist self, could be used by individuals, such as Lister and the Chevalier d’Éon, to support the idea that their internal desires, no matter how opposed to societal norms, were the guide to their true and authentic self.[i]

[i] Anna Clark, Alternative Histories of the Self: A Cultural History of Sexuality and Secrets, 1762–1917(New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017).

14 Emma Donoghue also contested the idea that “only after the publications of late-nineteenth-century male sexologists such as Havelock Ellis did words for eroticism between women enter the English language.” She explains that her work is “urgently committed to dispelling the myth that seventeenth- and eighteenth-century lesbian culture was rarely registered in language and that women who fell in love with women had no words to describe themselves.”[i] Donoghue argued that the abundant evidence she had uncovered did “not seem to refer only to isolated sexual acts, as is often claimed, but to the emotions, desires, styles, tastes, and behavioural tendencies that can make up an identity.”[ii]

[i] Donoghue, Passions between Women, 2-3.

[ii] Donoghue, Passions between Women, 3.

15 Martha Vicinus and Valerie Traub made similar arguments.

16 More recently, Jen Manion, in Female Husbands, shows a similar influence of cultural texts on the ability of individuals who transed gender in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The cultural texts were different from those of later periods, leading to different self-understandings, but the process is similar to what we associate with identity formation around cultural texts from the late 19th century forward.

17 Harry Oosterhuis has added to this framework – with his work on John Locke, and the implications of Locke’s idea of possessive individualism – Oosterhuis documents examples of individuals throughout the eighteenth century who argued for the right to do as they pleased with their own body, based on a Lockian understanding that the individual owns their own body – as opposed to God or the church. Oosterhuis finds this attitude among the lower classes, among those with greater resources, and among the men of the molly houses.

18 This understanding of identity formation in the eighteenth century is entirely compatible with most of the Foucauldian framework as it is currently understood – I argue – so long as we focus on the theory of power – and the concept of biopower – that runs throughout Foucault’s major works. Early in the History of Sexuality, Foucault states that the type of power he is most interested in was manifest early on in the medieval courts – There, individuals assumed identity categories (of plaintiff and defendant, for example) and submitted to a body of power/knowledge – the law – which could compel individuals to act in desired ways. Individuals were coerced by this system, but they also consented to it, based on the expectations of benefits that might be derived from doing so. Acceptance of the idea of the courts masked the scope of this new intrusion of power into the lives of individuals, and moved the society in a direction that was in the interests of the state. The real break with the past within Foucault’s theory of power occurred in the late seventeenth century – when certain societies begin to generate sufficient surpluses that the manipulation of those surpluses, the incentivizing of some behaviors, and the disparaging of others, became a regular tool of state policy – The birth of biopower and biopolitics. There is nothing special about the late nineteenth century in Foucauldian understanding of power – it is simply a point within the continuing thickening of the web of discourse and biopower, a process largely continuous if also uneven from the late seventeenth century to the present. The number of incentives, of regulatory discourses – that an individual was subject to multiplied as the decades progress, coming from a law, a tax, an advice manual, a fashion magazine, a school curriculum – multiplying the rules for being a “good wife” a “marriageable daughter” a “respectable man” a “good citizen” or a “man of fashion.”

19 Individuals combined cultural texts – to create usable understandings of themselves and their desires – Some of these constructions were fleeting – dying with the individuals who formulated them – while others got picked up and passed on – either in a subculture – like in the molly houses – or in smaller communities, such as those described by Martha Vicinus – or in the larger culture – such as in the cultural category of “female husband” or the molly – which some individuals read about in the newspapers, recognizing themselves in the process.

20 Some of these cultural texts were used to describe only superficial tastes, while others were used by individuals to explain something more fundamental about themselves.

21 Rather than looking for a particular moment of transition for the whole society, it might be better to think about multiple ways self-understandings developed and dissipated – with scholars working to document these “effervescent bubbles” – if you will – of self-understanding – that appeared and disappeared within the thickening web of cultural discourse from the late seventeenth century forward.

22 This cultural history approach has also been dominant in the best work on sex between men since the 1990s, but it has by and large only been applied to the period from the late nineteenth century forward. George Chauncey’s 1994 Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 was internationally influential for its thoroughness and originality.[i] Building out from the experience of working-class and other individuals, Chauncey expressed skepticism over “some recent social theories” that had attributed “almost limitless cultural power” to medical discourse, arguing instead that “the invert and the normal man, the homosexual and the heterosexual, were not inventions of the elite but were popular discursive categories before they became elite discursive categories.”[ii] Chauncy left the door open to the possibility of continuities between his evidence and the eighteenth-century molly houses of London, but the ability to make such connections, he argued, fell out of the scope of his study, and it “will take another generation of research” before such connections might be made, even as “we should never presume the absence of something before we have looked for it.”[iii] The chronology of Chauncey’s study reinforced the growing emphasis on the importance of a late nineteenth century as a transitional moment, even as he stressed the unevenness of the processes of change across the categories of class, race, and ethnicity, playing out over decades.[iv]

[i] George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Makings of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 1.

[ii] Chauncey, Gay New York, 5-6, 27.

[iii] Chauncey, Gay New York, 12.

[iv] See also Chauncey, Gay New York, 27.

23 Much of the later scholarship, also grounded in the methodologies of social and cultural history, such as Matt Houlbrook’s Queer London, Matt Cook’s Queer Domesticities, and Margot Canaday’s The Straight State would mirror Chauncey in showing the long and uneven process of the homosexual/heterosexual binary supplanting earlier ways of understanding same-sex desire.[i] But all of these works showed that unevenness playing out between the late nineteenth century and the mid twentieth century, without sustained discussion of what occurred before. Most social and cultural historians writing on sex between men in the early twenty-first century did acknowledge the starkly different findings of lesbian history, but rather than working through how this might be compatible with their findings, many instead observed that because “lesbianism remained invisible in the law and, in consequence, in the legal sources,” lesbian history “demands its own study.”[ii] Accurate in many ways, such observations also elided underlying methodological unities, based on cultural history practices, that might have brought together “the new gay history,” as the newer twenty-first century work was dubbed in a Journal of British Studies review article, and lesbian histories.[iii] Pointing out these broader continuities is not meant to indicate that nothing new or significant occurred in the late nineteenth century, but it is meant to argue that what that was had more to do with liberal politics than is currently acknowledged. The word “homosexual,” like the term “urning” before it, was originally crafted to identify a new kind of subject within liberal political debate. When thinking about why such terms and concepts – and especially “the homosexual” – might become more prominent, and even hegemonic for a time, within this process – we need to think about two contextual elements that also date from the late seventeenth century – the liberal pubic sphere, and liberal political systems.[iv]

[i] Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 (University of Chicago Press, 2006); Matt Cook, London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885-1914 (Cambridge University Press, 2003); Margot Canaday, The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America (Princeton University Press, 2009). Other works by historians from this same period, showing this same pattern, include Laura L, Doan, Fashioning Sapphism the Origins of a Modern English Lesbian Culture (Columbia University Press, 2001); Sean Brady, Masculinity and Male Homosexuality in Britain, 1861-1913 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005); Morris B. Kaplan, Sodom on the Thames: Sex, Love, and Scandal in Wilde Times (Cornell University Press, 2005).

[ii] Houlbrook, Queer London, 10.

[iii] Joseph Bristow, “Remapping the Sites of Modern Gay History: Legal Reform, Medico‐Legal Thought, Homosexual Scandal, Erotic Geography,” Journal of British Studies 46, 1(January 2007), 120.

[iv] Liberal political thinkers who have written works on both on liberal political systems and the type of education needed to create subjects able to sustain such systems include Locke, Rousseau, Wollstonecraft, and Freud [Eros and Civilization and Three Essays on a Theory of Sexuality]. In his most recent work, only published a few weeks ago, Harry Oosterhuis is moving towards addressing these connections between eighteenth-century liberalism and arguments for the social acceptance of “sodomites.” See Harry Oosterhuis, “Sodomy, Possessive Individualism, and Godless Nature: Eighteenth-Century Traces of Homosexual Assertiveness,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 32 3(September 2023): 288-312.

24 A free press developed in this period – as necessary to sustain the commercial society that provided the tax base to sustain the wars that preserved the Glorious Revolution – This was no altruistic gift from the state, as it was only though granting greater autonomy in the economic sphere, and the freer flow of information that that required, that it was possible to generate the increased wealth that sustained the state. The establishment of partisan politics within a representative system of government has received less attention in relation to the history of sexuality – but, building on Faramerz Dabhoiwala, I argue that it is nearly as important – Why this is so is indicated in Seymour Dresher’s Abolition – In this work, Drescher examines every abolition of slavery that occurred without warfare – and finds that the critical element was a functioning public sphere – and liberal political systems that responded to public pressure.[i] – Slavery, as with other systems of oppression, pre-dated the establishment of the liberal public sphere and representative political systems. But once such systems were established – moral arguments could gain ground, first in public debate, and later as a basis for political action – creating the conditions for overcoming injustice.

[i] Seymour Drescher, Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

25 Similar arguments have been made about challenges to the oppressions of women – first contested and debated in the liberal public sphere in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – leading to reforms within political systems in the nineteenth century.

26 We can see this process at work – starting in the late seventeenth century – around sexuality as well. No political faction championed the tolerance of same-sex desire – but accusations of it were used by one side against another – Accusations of same-sex desire were made against William of Orange by those who detested his religious, military, and economic policies – The privately funded molly house raids were meant to embarrass the government for not doing enough to prosecute vice – Such activities led to backlashes against overly-intrusive and moralistic policing – and this also led to public discussions of what an acceptable punishment for sex between men might instead be.

27 My current book project takes in these earlier debates – but centers on the 1770s and 1780s as the first point when we can gauge the success or failure of a range of arguments related to sex between men within this public debate – And these debates matter, because certain public arguments could be the basis for changing the laws criminalizing sex between men, while other public arguments were wholly rejected as the basis for such a reform. Arguments based on practices in the ancient world, and the acceptance of certain forms of same-sex sexuality within the ancient world, were not effective political arguments, even as such arguments might have helped individual elite men and women to act privately on their desires. Perhaps the greatest difference between the ancient world and the modern in Europe was the adoption of Christianity, and the reshaping of the norms of society around that belief system. The rise of moral philosophy in the context of the Enlightenment should not be seen as a refutation of that Christian belief system – certainly not in Britain, as Roy Porter so elegantly demonstrated decades ago, but rather as an attempt to create a more secular, abstracted, and universal version of that Christian ethical system, subjecting Christian teachings to logical testing and reasoned analysis, keeping those elements that proved beneficial, and modifying or discarding those that did not.[i] Moral philosophy subjected the ethical teachings of Christian theology to questioning and testing, even as core ideas from the Christian tradition remained embedded in Enlightenment ethical arguments. Works such as The Theory of Moral Sentiments, it has long been observed, are in fundamental ways abstracted from Christian thought. To individual such as Uday Singh Mehta, primarily grounded in different cultural and ethical traditions, the bounded universal subject that is the starting point for Locke and so many other Enlightenment philosophers reads as a secularized version of the Christian soul.[ii] In relation to same-sex desire, the pervasiveness of Christian ethics after the fall of Rome has been treated primary as a problem to be overcome, because it led to the religious condemnation of sex between men. But a more fundamental tenant of the Christian legacy had a potentially far more positive impact, at least within the context of liberal political systems and liberal pubic spheres, as they began to develop in Britain and elsewhere from the late seventeenth century forward. Secularized by, and imbedded in, liberal political systems (and the Enlightenment philosophies that underpin them) is the Christian concept of everyone as a soul of worth, equal to any other, in either the eyes of God or (at least ideally or theoretically) the rules of man. Of course – those societies were rampant with legalized discrimination, differential rights, and enslavement, but the promise of that inherent equality was still there, and could be and was built on, such as in the movement to abolish slavery, and in the movement to remove legal restrictions on women.[iii] Similar ethical arguments could and were made related to men who had sex with men, but they would only be successful once it was clarified what was being defended. Some early forays into this – such as the 1749 defense of pederasty briefly described above – were rejected. The arguments that gained adherents, first within debates like the one of the 1772 (described above) and later within liberal political systems, were the ones that focused on the right of the individual to engage in acts of their choosing that hurt no one else. These arguments depended on a liberal understanding of the self, and a liberal political system that recognized such individuals.

[i] Roy Porter, The Creation of the Modern World: The Untold Story of the British Enlightenment (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 2000).

[ii] Uday Singh Mehta, Liberalism and Empire: A Study in Nineteenth-Century British Liberal Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

[iii] Philippa Levine, Victorian Feminism, 1850-1900 (University of Florida Press, 1989), Judith Walkowitz, City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1992).

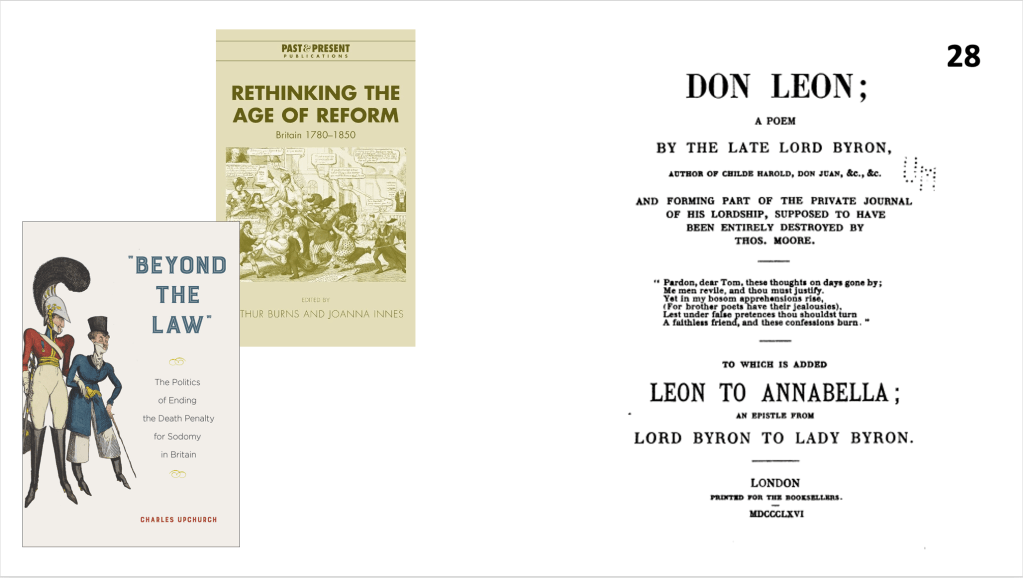

28 The attempt to lessen the penalties for sex between men through parliamentary legislation that occurred in the early nineteenth century in Britain, described in my previous book, ultimately won the support of a majority in the House of Commons, if not the Lords, in 1841. This success was not achieved through an argument for bringing pagan practices into the present, but in recognizing that the protections of liberal inclusion should be extended to individuals who desired members of their own sex.

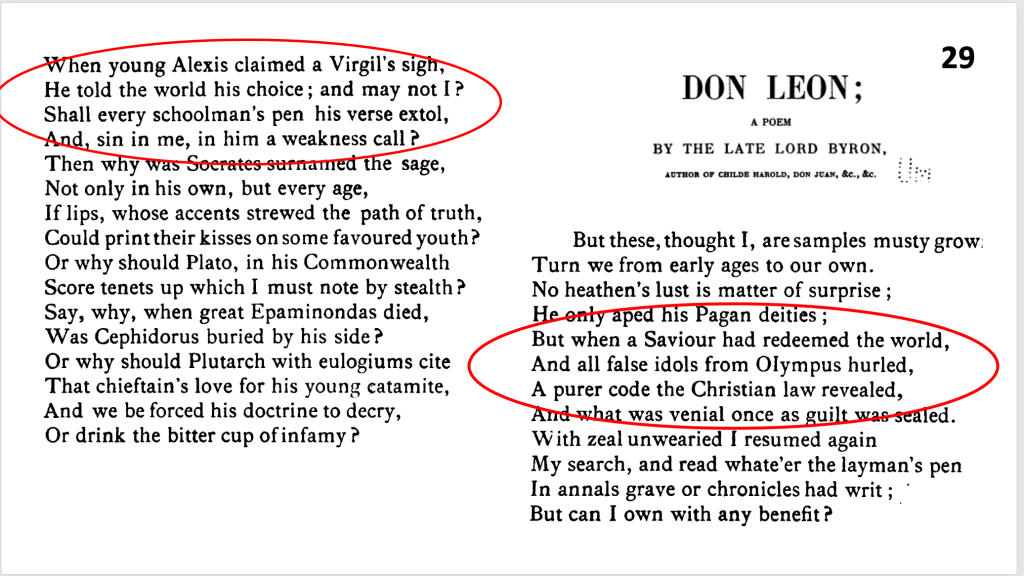

29 In one remarkable document – a fifty-page epic poem – produced as a part of that political debate, the protagonist grapples with his internal desires for members of his own sex, and observes that ancient authors and statesmen who have been praised for centuries also engaged in such sexual acts. But the anguished protagonist specifically writes that this is not sanction enough, that pagan practices cannot be copied, because a better moral code, based on Christian ethics, has supplanted ancient practice. What follows is not a rejection of Christian teaching, but a search for a path forward that embraces Christianity and the natural desires of this particular individual, as well as his right to be recognized as an equal subject within a liberal political system.[i] The ancient world allowed for slavery. The ancient world allowed the paterfamilias power of life or death over everyone in his household. His pleasure and desire mattered, and those of others did not.[ii] One of the greatest innovations in Christian ethics was to define such a situation as immoral. Enlightenment thinkers concurred. A great many moral philosophers and even religious thinkers questioned whether Christianity really had a fundamental problem with pleasure. None questioned the fundamental equality of souls, or the secular individuals that were based on them. Many ancient sexual practices involved sex without consent, subordinating the humanity of one individual for the pleasures of another. No argument for moral reform could condone such behavior, or make a moral case for it, either by Enlightenment or Christian ethical standards. A new term was needed – “homosexual” – to denote something new – something not present in the ancient world.[iii] It denoted someone for whom feelings of same-sex desire were natural, but also someone whose natural feelings were within the bounds of fundamental Enlightenment and Christian ethical practices. Elements of ancient sexual practice were drawn on to enhance these arguments, but pagan practices were rejected when they conflicted with the Christian and Enlightenment imperatives of the ethical treatment of others. Pederasty remained a word in circulation, and it was always something different, something morally compromised by contemporary standards, and something inherently unethical, based on the lack of consent it implied, and the erasure of one individual for the pleasures of another. While the age of consent has fluctuated over time, the fundamental principle that there is an age of consent has remained stable within the culture examined here for hundreds of years.[iv]

[i] Don Leon; A Poem by the Late Lord Byron . . . to Which Is Added Leon to Annabella: An Epistle from Lord Byron to Lady Byron (London: Printed for the Booksellers, 1866); Upchurch, ‘Beyond the Law,’ chapter five.

[ii] Craig A. Williams, Roman Homosexuality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[iii] On the origins of the term “homosexual” Robert Beachy, Gay Berlin: Birthplace of Modern Identity (Vintage Books, 2014); Ralph Matthew Leck, Vita Sexualis: Karl Ulrichs and the Origins of Sexual Science (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2016).

[iv] Louise Jackson, Child Sexual Abuse in Victorian England (New York: Routledge, 2000). Rachel Hope Cleves, Unspeakable: A Life Beyond Sexual Morality (University of Chicago Press, 2020).

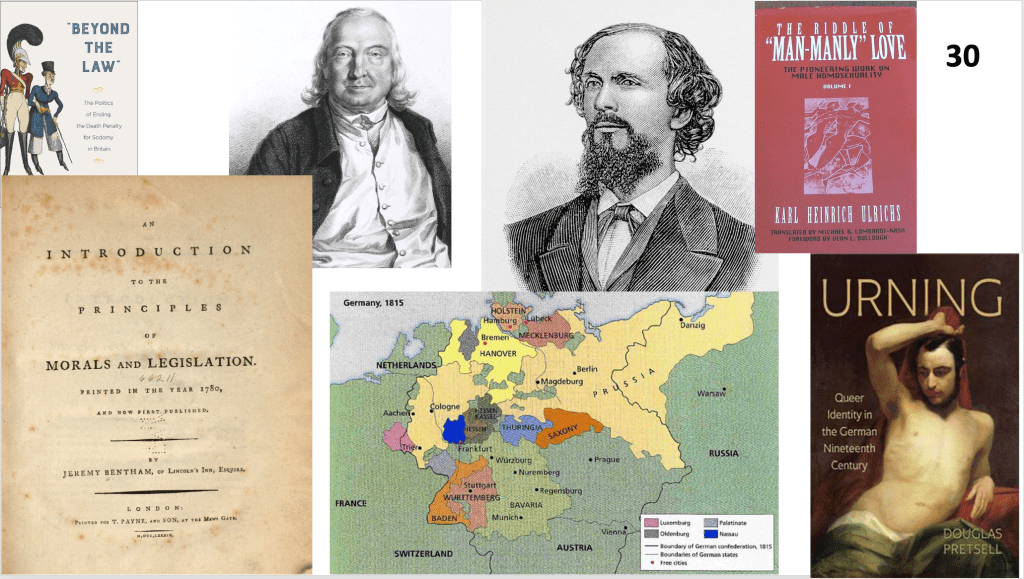

30 A moral argument for the rights of the homosexual could and did gain traction, within the public sphere, and eventually within politics and legislation, overturning discriminatory laws. To publicly declare oneself homosexual was a political statement. It was profoundly radical for its time and place.[i] Medical discourse propagated that term, but its fundamental characteristics were set in the context of a political debate, in the German states, more than a decade before. There was always a far greater diversity of sexual expression and gender identity expression within the lived experience of individuals, which was not adequately encompassed by the term “homosexual,” as evident in works such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis, where he documented a vast range of sexual pleasures, and coined many terms for them, few of which are still remembered.[ii] The cultural emphasis on the term “homosexual” was in part due to the fact that adopting it might bring profound political benefits.[iii] This political aspect to the “type” of person represented by the homosexual is what has been missing from our discussion of the origins of the term. More than a medicalized identity, from the start it was a political one

[i] Charles Upchurch, “Queers, Homosexuals, and Activists in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain?” Notches: (Re)Marks on the History of Sexuality, a peer-reviewed online publication of the Raphael Samuel History Centre, UK, July 28, 2015. http://notchesblog.com.

[ii] Harry Oosterhuis, Stepchildren of Nature: Krafft-Ebing, Psychiatry, and the Making of Sexual Identity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

[iii] Charles Upchurch, “Following Anne Lister: Continuity and Queer History Before and After the Late Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 26 4(September 2022): 400-414; and chapter six of Upchurch, ‘Called It Macaroni.’

31 This is why we need to recover the first public arguments for lessening penalties for sex between men in the 1770s. We need to analyze these first arguments, recognizing how they succeeded or failed in the public sphere, in a way similar to arguments around women’s emancipation, and for fight to end slavery and then address racial justice, and to improve the plight of the lower classes. All of these issues, race, class, gender, and sexuality, emerged as points of debate in the liberal public sphere as it was taking shape, from the late seventeenth century forward.[i] The Foucauldian model of identity formation can be extended back into the eighteenth century – it is, at its core, the method that cultural historians, and especially historians of same-sex desire between women, have been successfully using in that period for decades.

[i] Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1989); B. G. Carruthers, City of Capital: Politics and Markets in the English Financial Revolution, (1996).